When a doctor tweeted that she was “sexually assaulted” by a World Health Organization staffer at a Berlin conference in October, the U.N. agency’s director-general assured her that WHO had “zero tolerance” for misconduct.

WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said he was “horrified” by the accusations of groping and unwelcome sexual advances and offered his personal assistance. WHO suspended the staffer and opened an investigation.

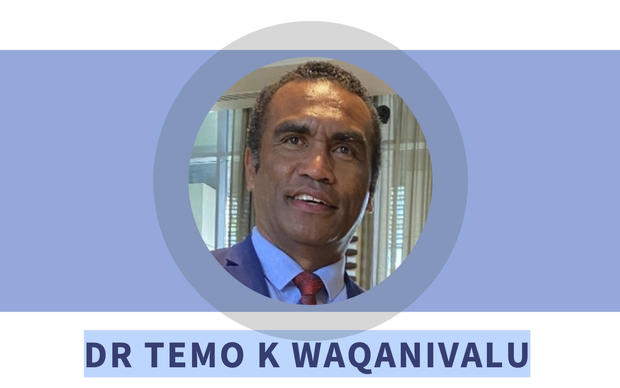

But internal documents obtained by The Associated Press show the same WHO staffer, Fijian physician Temo Waqanivalu, was previously accused of similar sexual misconduct in 2018.

A former WHO ombudsman who helped assess the previous allegation against Waqanivalu said the agency had missed a chance to root out bad behavior.

“I felt extremely angry and guilty that the dysfunctional (WHO) justice system has led to another assault that could have been prevented,” said the staffer, who spoke to the AP on condition of anonymity for fear of losing their job.

The previous allegation didn’t derail Waqanivalu’s career at WHO. As the new accusation surfaced, he was seeking to become WHO’s top official in the western Pacific with high-level support, documents show.

AP

In the coming weeks, the agency’s highest governing body is meeting to set public health priorities and may discuss how and when the election for the region’s next director might occur.

Waqanivalu hung up when the AP contacted him for comment.

He “categorically” denied that he had ever sexually assaulted anyone, including at the Berlin conference, according to correspondence between him and WHO investigators that the AP obtained.

WHO said its report into the Berlin conference complaint “is in its final stage” and would soon be submitted to Tedros.

On Wednesday, hours after this story was published, WHO told staffers it was forming a committee on “formal complaints of abusive conduct,” according to an internal email. The committee is to include 15 staffers, most of them designated by the U.N. agency’s director-general.

The claims against Waqanivalu are the latest in a series of misconduct accusations at WHO. The agency’s last regional director in the western Pacific was put on leave in August, months after AP reported that staffers had accused him of abusive behavior that compromised the U.N. agency’s response to COVID-19.

The earlier accusation against Waqanivalu came after a 2017 workshop in Japan, where a WHO employee said Waqanivalu had harassed her at a post-work dinner.

“Under the table, (Waqanivalu) took off his shoes, lifted one of his legs and toe(s) between my legs,” the woman wrote in a 2018 report that was shared with senior WHO officials.

She left the restaurant and said Waqanivalu followed her. After she said goodbye, Waqanivalu “proceeded to give me a hug, grabbing my buttocks with both of his hands and trying to kiss my lips,” the woman said. The AP does not typically name people who say they have been sexually harassed unless they come forward publicly.

After submitting her confidential report to WHO in July 2018, the case was “tossed around in (Geneva) for months,” one of the ombudsmen wrote to the woman in an email.

The woman was later informed that Waqanivalu would be given an “informal warning” and that the case was considered closed. She wrote in an email to a WHO ombudsman that the agency’s ethics office told her that pressing for an investigation might not be her best option.

In October, Waqanivalu sat on a panel at the World Health Summit in Berlin as part of a high-level conference with attendees including WHO chief Tedros.

In a hotel lobby one evening, numerous people were having drinks, including Waqanivalu and Dr. Rosie James, a young British-Canadian physician and former consultant for WHO.

“We were talking about his work at WHO and he just started putting his hand on my bottom and keeping it there,” James told the AP.

James said Waqanivalu “firmly held my buttock in his hand multiple times (and) pressed his groin” into her. Before Waqanivalu left, she says he repeatedly asked for her hotel room.

Later that night, she tweeted about the encounter, prompting WHO chief Tedros to pledge to do “everything we can to help you.”

James said WHO investigators interviewed her, but that Tedros never followed up. WHO offered to pay for any private therapy costs linked to the incident, James said.

In Waqanivalu’s interview with WHO investigators, he said he greeted James “by tapping her on her left upper arm,” according to a record of the discussion obtained by AP. He acknowledged asking for her hotel room number, saying he made the request “to connect, if need be.”

Waqanivalu told investigators he believed people in the group, including James, “were under the influence of alcohol.”

Last fall, Waqanivalu, who oversees a small team in non-communicable diseases at WHO’s headquarters, put himself forward as a candidate to be WHO’s next director for the western Pacific.

“The experience and expertise I have gathered over the years … have given me the relevant credentials,” Waqanivalu wrote in a September letter to Fiji’s then-Prime Minister.

About a week after the Berlin conference, the chair of WHO’s top governing body in the region told Waqanivalu in a message seen by the AP that his name was mentioned “as a potential candidate” to be the next regional director.

“That would be an opportunity for you, Dr. Temo,” Waqanivalu was told.

A memo from the prime minister’s office dated Oct. 17 confirmed “Fiji’s proposed candidacy” of Waqanivalu to the position.

A WHO-produced election-style campaign brochure created in September outlined Waqanivalu’s vision.

“Under my leadership, WHO will empower people to serve within their countries,” the document reads.

Paula Donovan, co-director of the Code Blue campaign, which seeks to hold U.N. personnel accountable for sexual offenses, said the allegations regarding Waqanivalu were deeply worrying.

She said it was particularly concerning that an official accused of sexual harassment had been potentially in line for such a prominent leadership role and that WHO had failed to uphold its own “zero tolerance” policy for unprofessional behavior.

“It’s patently false that WHO does not condone sexual misconduct,” Donovan said, calling for its member countries to overhaul the agency’s internal structures so that its officials are held accountable. “When WHO keeps this kind of stuff under wraps, they are giving sexual predators carte blanche to do it again with impunity.”

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal