When medic Jonathan Hollins arrived on a remote South Atlantic island, he discovered to his horror his celebrity patient was dying. Old age, dwindling eyesight and a poor diet had left him weak and near to starving. This was no ordinary VIP though.

Hollins’ patient was an ancient Seychelles tortoise – also called Jonathan – who was just five when Queen Victoria ascended the throne and 120 when the late Elizabeth II became monarch. Now aged 192, he is believed to be the world’s oldest living land animal.

Yet when 52-year-old Hollins arrived at St Helena in 2009, the slow-moving reptile was apparently on his last legs. His beak was soft and crumbly, he had cataracts and existed on a diet of dirt, dry leaves and grass.

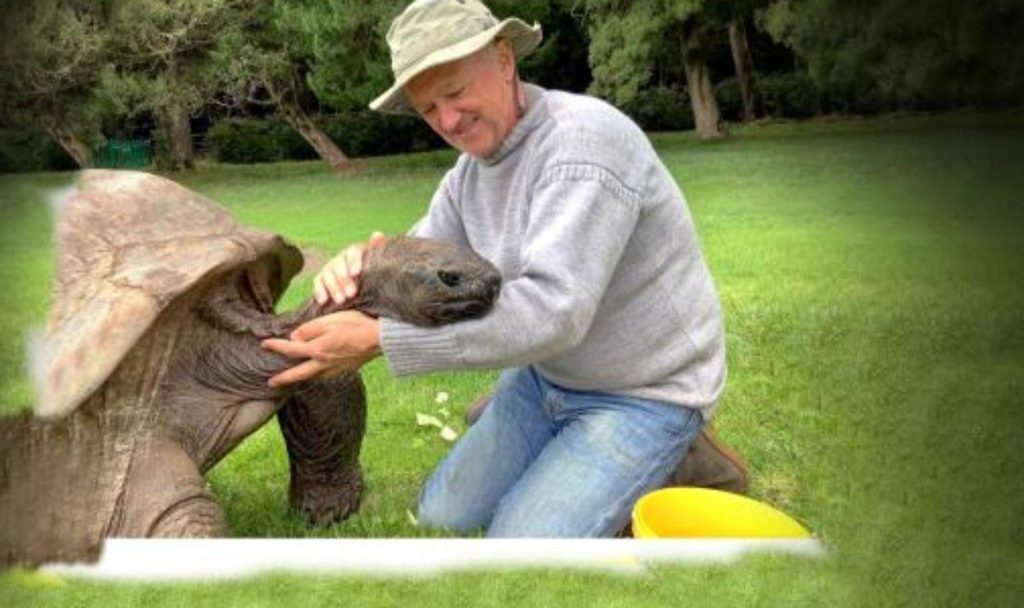

After observing him for hours in the verdant gardens of Plantation House, a grand 18th-century residence that is home to the island’s governor and his wife, Hollins realised Jonathan was dying of starvation.

Now 65 and newly-retired, Hollins has written an entertaining memoir about his time as the first permanent vet based on St Helena, 1,200 miles off Africa’s west coast and 5,000 miles from Britain.

The world’s second most remote inhabited island, it’s where Napoleon was exiled after losing the Battle of Waterloo.

And it’s fair to say Jonathan, born just 11 years after Bonaparte’s demise, remains alive today thanks to Hollins’ intervention.

“Giant tortoises are almost considered quasi-immortal in that they tend not to die through severe metabolic disease or cancers as we do – they wear out and Jonathan was a classic example,” he explains.

The consequences were grave. Jonathan is an island icon, a worldwide symbol of longevity marked by Guinness World Records. When his death does eventually happen, a meticulously planned “Operation Go-Slow” protocol, complete with an obituary and details of how to preserve the 28-stone tortoise’s shell, will be enacted to honour his VIP status.

So it’s not hard to imagine what a blow the death of this important biological specimen, also the island’s most important tourist attraction, would have been. Every Sunday, Hollins visited Plantation House and hand-fed the tortoise carrots, apples, cabbage and cucumber with his friend’s dog, Che, in tow.

“His beak regrew and became super sharp again, and he became more active and put on weight,” says Hollins. “What he was missing was vitamins, minerals, and trace elements, the vital ingredients for metabolism.”

Jonathan’s miraculous revival is one of several of Hollins’ heroics which he recounts in his new book, Vet At The End Of The Earth, a memoir of his veterinary adventures in British Overseas Territories including the Falklands Islands and Tristan da Cunha.

Hollins writes with wit about relocating herds of reindeer, attacking a chicken-killing parasite and rescuing a missing dog from a cliff edge.

And he’s equally warm and funny in person when we meet on a sunny autumn afternoon just weeks after his retirement from St Helena. Sporting a bronzed complexion from years spent outdoors, Hollins has an untamed spirit, one unlikely to disappear as he plans on returning to St Helena each year to live as a semi-permanent resident.

He was born in London at the University College Hospital where his mother worked as a theatre sister – his father was an engineer “who worked behind the Iron Curtain a lot in the 1950s and 1960s”.

Hollins was raised in Surrey with his brother surrounded by chickens, rabbits, geese, dogs and cats and planned to become a vet until his school career advisor talked him out of it. While studying economics at Cambridge University, he was urged by his rowing teammates, some of whom were veterinary science students, to switch courses and follow his passion. Early on in his career, he worked as a vet in South Africa and joined a Zimbabwean archaeological expedition as a medical officer. His experiences abroad shaped him immeasurably.

“Travel genuinely broadens your mind and makes you less parochial and therefore more tolerant of race, colour, creed, religion and gender,” he explains.

Despite his wanderlust, he spent two decades working in the south of England, beginning with three years at what was then the only vet practice in Wellingborough, Northants.

“We had an abattoir, which was not my favourite word, but it was very good money,” he says. As Hollins was a generalist, his segue into island veterinary practice was never a daunting feat.

It was a one-month locum post covering for a friend in the Falklands that eventually led him to St Helena, a “mini Galapagos” with 250 unique species, equivalent to one-sixth of the UK’s total endemic biodiversity.

He became the island’s first permanent vet after sending his CV to St Helena’s governor. Top of his priorities, aside from saving Jonathan’s life, was rescuing the St Helena plover bird, its national pride. Roaming feral cats had hunted the endemic species to near extinction and it was Hollins’ job, with the help of para-vets he trained – the animal equivalent of paramedics – to euthanise the pitiful moggies humanely.

Aside from routine neuterings and surgeries, Hollins conducted autopsies regularly for scientific research. And then there were the downright bizarre jobs. Once a year, he joined St Tristan’s natives for “ratting day”. The annual competition was borne from islanders’ attempts to reduce the rat population but today involves docking as many rat tails as possible – without killing them – in a bonding exercise for the community. Hollins judges the prize for the longest tail.

But Jonathan was always his star patient.

“I really bonded with him,” he says. “He recognises my voice. I don’t think it’s love, it’s food – it’s a Pavlovian response – but I love that. I’ll stroke him and warm his neck and he loves it. “He’s very gentle unlike his male counterpart, David, who is really aggressive.”

There are four tortoises on the island: Jonathan and relative youngsters David, 54, Fred, 51, and Emma, 54. Last year David upturned Fred, who has mobility issues, after he emerged from a mud pool.

Hollins arrived to find him helpless on his back, legs sprawled in the air.

“David was just there, gloating, the potential murderer!” Hollins cries.

Thankfully, he managed to rock Fred a few times before flipping him over, thus saving his life. But this was not David’s first attack.

Several years earlier, he targeted Jonathan as the elder tortoise munched on his food unaware of the “200-kilo battering ram” headed towards him. “He rammed Jonathan almost head-on and flipped his neck up in the air,” recalls Hollins.

“It was slightly oblique otherwise David would have severed Jonathan’s neck and killed him. It absolutely terrified me.”

Poor Hollins suffered so many near-death scares with Jonathan, it’s a wonder his nerves aren’t shredded. On another occasion, a jogger telephoned him to say Jonathan was lying dead, spreadeagled on Plantation House’s paddock. Fearing the worst, Hollins raced there to find his leathery friend doing a “good imitation” of death.

“He was flopped out completely,” says Hollins. “It’s amazing how tortoises draw their legs inside their shell.” Before mentally putting Operation Go-Slow into action, he realised the tortoise’s eyes were shut, in fact, signalling he was alive. He gently prodded Jonathan’s sinewy neck and to his delight, the tortoise’s eyes flicked open.

“I was so happy I almost cried with relief,” Hollins recalls. “I gave him a big hug. It was like disturbing a grumpy old great-grandfather having a snooze in the afternoon.”

I

t transpires Jonathan had been sunbathing, a behaviour common among cold-blooded reptiles but one not often observed among tortoises in warmer climates. However, St Helena, where Jonathan first arrived in 1882 as a gift for the governor, has cold and damp wintery days and this was his way of remedying that.

Today, Hollins’ ex-girlfriend, who goes by the name Teeny Lucy for her petite frame, cares for the four tortoises. St Helena has yet to find a suitable replacement for him. It’s home to just 4,300 people but island life is not for everyone. “There are some people that didn’t last six months,” he says.

“They didn’t realise what living on an island is like. You don’t have coffee shops and restaurants and the shops run out of things. Then there’s the tyranny of isolation.”

Over the past year, cargo deliveries have been late several times.

“We ran out of milk, toothpaste and chocolate… and that was serious – the island was in desperation,” he laughs. The shortfall got so bad Hollins was forced to eat hated toffees and nougat he had left to linger at the bottom of assortment boxes. Yet he never lost his love of living among the elements.

“I love islands because they’re a microcosm of humanity,” he says. “It’s a crucible of what we are with all the challenges that go with it. And ironically, you’re walled in – not by walls but by the sea.”

Had he stayed in the UK, Hollins would undoubtedly have led a more comfortable life but he has no regrets. “I like investigations, I love the detective work, I don’t like managing a business, that’s not me,” he adds.

“And so to tie myself down in that way is difficult. I’ve lost out on other things like having children and so on… but I’ve enjoyed my life. And it’s been interesting.”

- Vet at the End of the Earth: Adventures with Animals in the South Atlantic by Jonathan Hollins (Duckworth, £16.99) is out now. Visit expressbookshop.com or call Express Bookshop on 020 3176 3832. Free UK P&P on orders over £25

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal