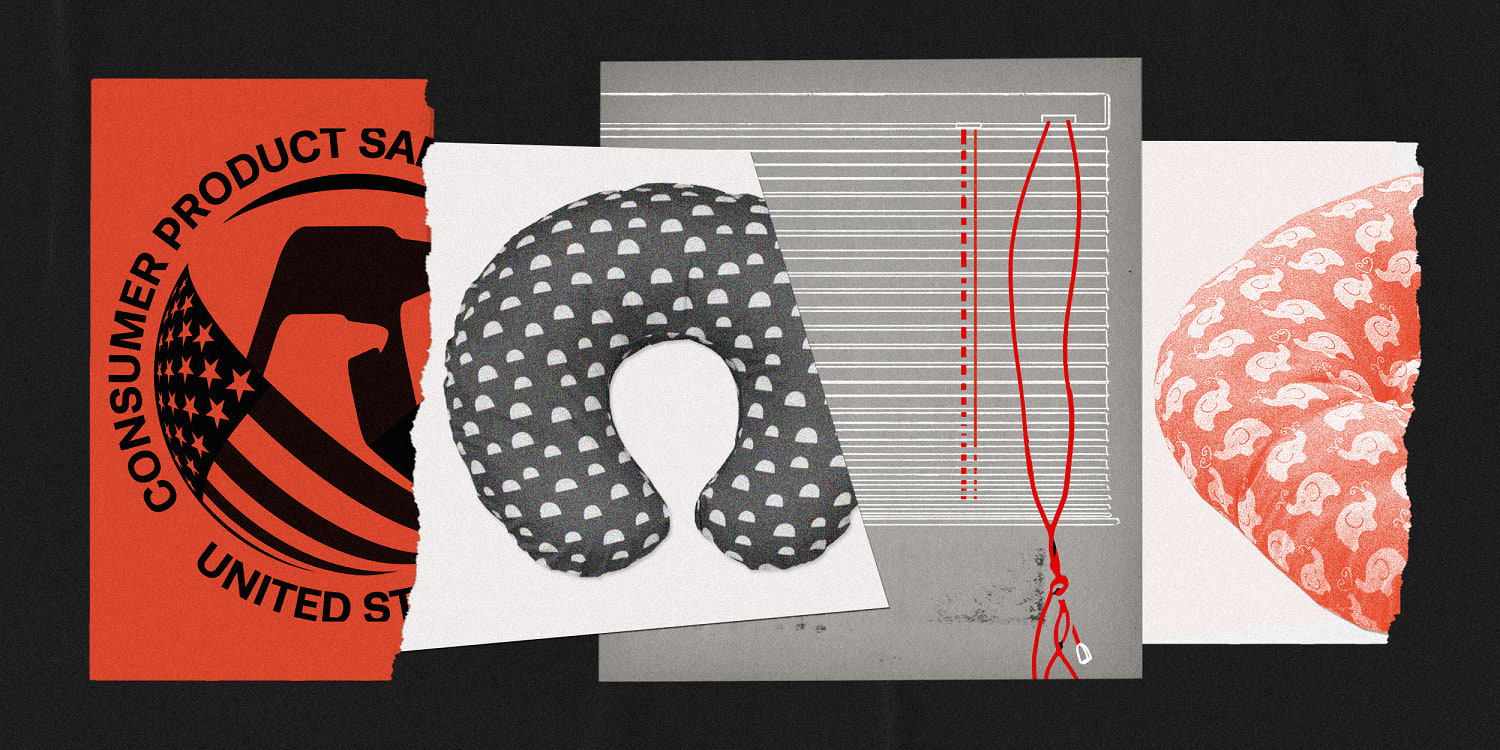

The federal agency tasked with protecting the public from hazardous products often knows about dangerous and deadly items for years before it takes action.

The Consumer Product Safety Commission, which oversees about 15,000 types of products, is constrained by a system that is slow to identify deaths and limits the federal government’s power over manufacturers, NBC News revealed in a yearlong project examining the agency.

Manufacturers say restrictions on the CPSC’s authority are necessary guardrails that protect against government overreach and help encourage the development of industry-led voluntary safety standards that are more effective than federal regulation.

But the limits facing America’s consumer product safety system also mean that it can take years, even decades, for safety requirements to be put into place.

As that process grinds on, some of the most vulnerable Americans continue to die from products that both regulators and manufacturers know to be hazardous, reporters found: Dozens of babies have died on infant loungers and nursing pillows, and hundreds of toddlers and young children have been accidentally strangled to death on the cords of window blinds, curtains and shades.

Here are five takeaways from NBC News’ reporting:

1) Death reporting lags behind

To justify a new rule or a recall of a hazardous product, the CPSC needs to have evidence that the product poses a risk to consumers — often relying on data that is incomplete and can be delayed for years, experts told NBC News.

Death investigations are usually the responsibility of state and local authorities, who do not always describe the role that a consumer product may have played in fatal incidents or include the product’s manufacturer or model. The CPSC has a program that allows medical examiners and coroners to quickly and directly report deaths to the agency, but participation is voluntary and submissions can be incomplete.

That leaves the CPSC to rely on outside sources like news clips, reports submitted by consumers, health professionals and local officials, and death certificates that lag months or even years behind. Under federal law, manufacturers are required to tell the CPSC when they receive information that a product could create “an unreasonable risk of serious injury or death,” but companies are not always forthcoming. The CPSC also conducts its own in-depth investigations into some deaths, which are time- and labor-intensive.

Such obstacles can end up delaying federal action, as well as the information that reaches the public about dangerous products, NBC News found.

To compile its own count of deaths related to nursing pillows and loungers, NBC News drew from incident data listed in two CPSC databases, the Clearinghouse and SaferProducts.gov. This data is often incomplete and limited, so reporters also relied on hundreds of public records requests and dozens of interviews with family members and attorneys, among other sources.

The CPSC periodically updates its own counts of product-related injuries and deaths based on new information that may come in long after the fact. In an investigation published this week, NBC News found that at least 440 children ages 8 and under were accidentally strangled to death on window covering cords from 1973 to 2022, according to a review of CPSC reports and data obtained through a public records request.

Shortly after NBC News published its story, the CPSC released new data showing that more deaths had occurred in recent years than the agency had previously reported. According to the new data, at least 16 additional children were strangled to death on window cords, raising the total death toll to at least 456.

Death by Delay

- Hundreds of children have been strangled on cords from window coverings in the past 50 years. Officials and manufacturers knew about the danger — why didn’t they do more sooner?

- Popular baby loungers are tied to more deaths than U.S. officials previously announced.

- Babies set to sleep on nursing pillows can stop breathing in minutes. Dozens have died.

- Federal officials want to repeal a law that delayed warnings about dangerous products.

2) Federal regulators may wait for a ‘body count’ before taking action

The lag in reporting to the CPSC can have a major impact, because the agency may hold off on pursuing a new safety rule or product recall until it has evidence that people are dying or being seriously injured. In practice, that can mean more people will be harmed before officials decide to step in, said Elliot Kaye, a Democrat who chaired the CPSC from 2014 to 2017.

“There has to be a body count before we can act,” he said in a recent interview. “And then that’s often not enough — because there are so many hurdles to overcome.”

Even once the CPSC decides there is enough evidence to take action on a product, the agency often begins by singling out one manufacturer at a time, rather than tackling the entire class of products immediately.

In September 2021, for example, the CPSC and The Boppy Company announced a recall of millions of pillow-like infant loungers after the deaths of eight babies — the first time that the federal government acknowledged deaths linked to the product. But soon afterward, the CPSC delayed a broader plan to regulate loungers and other infant cushions.

Yet babies had died years earlier in incidents involving loungers sold by other manufacturers. In May, NBC News reported that there had been at least 25 deaths since 2015, most commonly when babies suffocated or asphyxiated after being placed to sleep on the cushions, against manufacturers’ instructions. Infant loungers sold by at least four other manufacturers were involved in the deaths tallied by NBC News.

3) Critics say the CPSC is hamstrung by federal law

Even when the CPSC decides that a product is so hazardous that federal regulators need to intervene, the agency is constrained by laws designed to limit its ability to act on its own.

Under a federal provision known as Section 6(b), the CPSC must consult with manufacturers before disclosing information about specific products, even if officials deem the items so dangerous that the agency wants to issue a public warning or pursue a recall. No other federal health or safety agency is similarly restricted.

Industry leaders say that Section 6(b) — created under the Reagan administration — is a necessary backstop. The measure guards against “the release of incomplete or inaccurate information that creates unnecessary worry and confusion,” Lisa Trofe, executive director of the Juvenile Products Manufacturers Association, said in a statement.

But some Democratic lawmakers and CPSC commissioners are now calling for its repeal, blaming the provision for delaying public warnings about deadly products such as baby loungers and treadmills.

“It is an aberration — it is an isolated instance of industry throttling an agency,” Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., said earlier this year. Along with Rep. Jan Schakowsky, D-Ill., Blumenthal has introduced legislation to repeal Section 6(b), but it has yet to advance.

4) CPSC must show current standards fall short

Another Reagan-era provision gives manufacturers a way to head off mandatory safety rules: They can create a voluntary standard instead.

Voluntary standards are created outside of the federal government through a process that can proceed more quickly than federal rulemaking. While the effort is collaborative, typically involving the CPSC and consumer advocates, it is often led or heavily influenced by manufacturers.

If a voluntary standard is in place for a product, the CPSC must first determine whether it is effective and broadly adopted by manufacturers before the agency can create mandatory safety requirements.

That can contribute to delays in federal action and make regulators more cautious about pushing for mandatory requirements, current and former CPSC commissioners said. In some cases, regulators will wait for decades before moving forward with federal rules for common household products, even when young children continue to suffer gruesome deaths, NBC News found.

For example, the window covering industry spent many years regularly updating its voluntary standard for corded blinds, shades and curtains, making safety improvements in partnership with the CPSC. But the CPSC eventually determined that the voluntary standard failed to do enough to protect children and in 2022 issued its first mandatory rules — nearly 37 years after its first public warning about the hazard.

The industry immediately challenged one of the two new rules, focused on custom-made window coverings, saying that it was based on faulty analysis and would have a calamitous financial impact on some manufacturers. A federal court agreed that the CPSC hadn’t followed proper procedures and tossed the rule this fall, though the other CPSC rule focused on window coverings purchased off the shelf remains in effect.

The Window Covering Manufacturers Association, the group that sued the CPSC, said in a recent statement to NBC News that deaths are now “extremely rare” in the U.S. thanks to the industry’s voluntary standard.

The CPSC — which says that about nine children a year still strangle themselves to death on window cords — plans to propose a new mandatory rule next year.

5) Deaths can lead to action — but it takes time

Despite the regulatory barriers that it faces, the CPSC has stepped up its pursuit of mandatory rulemaking and unilateral warnings about product hazards.

“While reporting delays and regulatory requirements can at times significantly lengthen the rule writing process, the agency is committed to leveraging all of its authority to protect consumers,” the CPSC said in a statement.

In some cases, the CPSC’s action has come after news coverage, moves by lawmakers and pressure from grieving parents.

This summer, NBC News reported that at least 162 babies under a year old had died in incidents involving nursing pillows since 2007, but there were no federal safety rules for the popular infant product. The babies typically died from suffocation or asphyxiation after being placed to sleep on the pillows, which goes against manufacturers’ instructions.

The monthslong investigation revealed a significantly higher number of deaths linked to nursing pillows than the CPSC had publicly disclosed. To compile and corroborate its count of the deaths, NBC News relied on autopsies, death certificates, police reports and child welfare and health department records obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests.

NBC News used a similar approach to its investigation of infant loungers last spring, which also revealed more deaths than the CPSC had previously disclosed.

The CPSC recently began pursuing the first mandatory federal safety rules for nursing pillows and infant loungers, which would require significant design changes to both products with the goal of making them safer. The proposals are now going through the lengthy rulemaking process before being finalized, and it could be years before they take effect.

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal