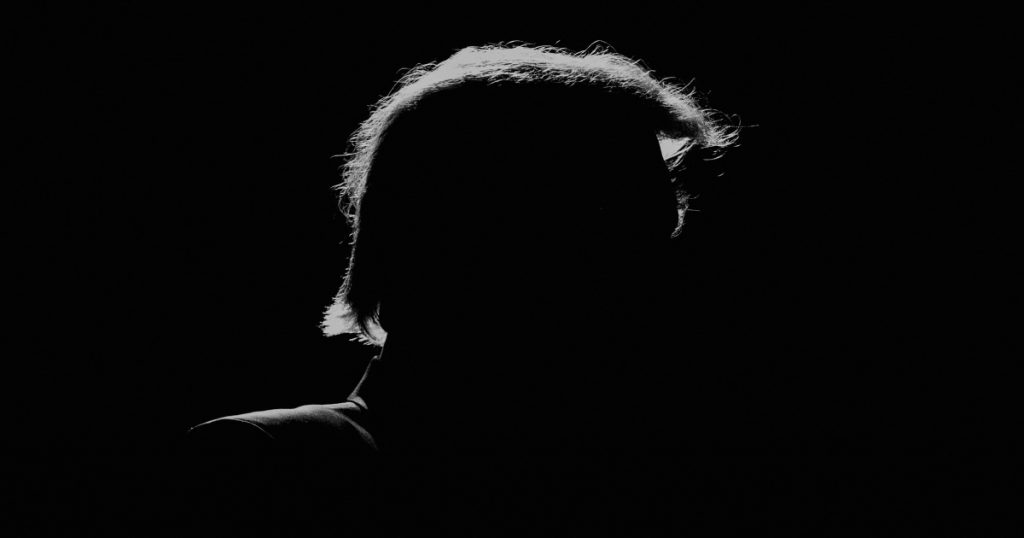

Donald Trump himself is, at the moment, only under criminal investigation, but on Tuesday, for the first time, a jury convicted the Trump Organization of being a fraudulent and felonious enterprise.

This was a signature achievement for Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg. His prosecutors just tossed the king’s brand from the throne. The $1.6 million fine the company faces is the least of the harm. From now on, the criminal convictions will place an indelible asterisk next to the Trump business name.

This was a signature achievement for Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg. His prosecutors just tossed the king’s brand from the throne.

The jury took about 10 hours over less than two days to deliberate and convict the company on all 17 counts of fraud, tax evasion and falsifying business records. Quick criminal verdicts can reflect the force of prosecutors’ evidence.

In this case, the Trump Organization’s former CFO Allen Weisselberg provided everything that was needed. With serious criminal investigations underway against Trump in Washington, Atlanta and New York, the convictions remind us of the sharpest arrow in a prosecutor’s quiver: flipping the target’s lieutenants.

Success with this begins with the serious investigatory groundwork that shows them that they face a long time in the clink unless they cooperate against the target’s higher up.

Weisselberg was a Trump loyalist for over 50 years, a virtual family “apprentice.” He wouldn’t have turned state’s evidence unless the Manhattan District Attorney’s office had him dead to rights.

Loyal to the end, Weisselberg never fingered Trump personally at trial and even cooperated with defense lawyers by forswearing Trump’s involvement in the fraud. Still, Weisselberg’s testimony was the centerpiece of the Trump Organization’s conviction because he laid out how he saved the company taxes.

For years, the Trump Organization ran a scheme to avoid taxes by compensating high executives off the books. Taxes owed to the people of New York were hidden under the table via unreported benefits of luxury apartments and cars and even private school tuition for relatives.

During the trial, the Trump Organization’s defense was trying to convince jurors that Weisselberg was a lone criminal wolf who concocted the scheme purely for personal benefit.

But as an alternate juror put it in an interview with The New York Times, the defense strategy failed to convince jurors that “Weisselberg did it for Weisselberg.” In fact, insulting the intelligence of the jury backfired, as it inevitably does. Common sense, always a strength of the jury system, confirmed that a company’s tax liability — and not just Weisselberg’s — dropped when it cooked the books to shrink its reported payroll.

The jury did not need to affirm Trump’s criminality to convict, but prosecutors in Washington, Fulton County, Georgia and within the Manhattan DA’s office are working overtime to build cases that could do just that.

Of course, the jury didn’t have to guess who was the primary beneficiary. Although Trump was not a named defendant, the prosecution went out of its way to insert Trump into the jurors’ minds, arguing in closing arguments that Trump explicitly sanctioned tax fraud and that “this whole narrative that Donald Trump is blissfully ignorant is just not real.”

The jury did not need to affirm Trump’s criminality to convict, but prosecutors in Washington, Fulton County, Georgia and within the Manhattan DA’s office are working overtime to build cases that could do just that. And this reckoning against Trump’s flagship company is sure to embolden them.

Prior to the convictions, DA Bragg had already seemed to be reviving his stalled criminal investigation into Trump personally by hiring Matthew Colangelo, a highly experienced Justice Department lawyer and complex white-collar fraud investigator. Before joining the top tier at DOJ, Colangelo led New York Attorney General Letitia James’ inquiry into Trump.

Trump could be forgiven just now for secretly wondering why he ever ran for president, even as he runs again, motivated partly, it appears, by its cherished immunity from prosecution. He got away with questionable financial conduct for years in New York before he took his misconduct to Washington and multiplied it several hundred times over.

By thrusting himself into the national spotlight, there is no way that his misconduct wouldn’t catch stellar prosecutors’ careful attention.

Trump never admits regret. But thoughts of it might be floating across his mind at Mar-a-Lago these days. With his company’s first conviction, they could be keeping him awake, along with the sound of closing walls.

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal