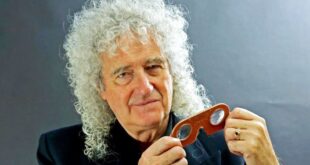

William Shakespeare’s First Folio (Image: Getty)

To be, or not to be… the most famous writer of all time. When it comes to William Shakespeare, that is not the question. The love that endures for England’s national poet, the son of a humble glove maker from the West Midlands, really does, in his own words, “put a girdle round the Earth”.

You need only witness the coach loads of fans from all over the UK, Europe, America and Asia descending upon Stratford-upon-Avon – The Bard’s birthplace and home of the Royal Shakespeare Company – to realise that people from every part of the world, even those who don’t speak English, are still enthralled by Shakespeare and his plays.

And yet, were it not for the actions of a couple of friends 400 years ago, many of his greatest works, including Antony and Cleopatra, Julius Caesar, Macbeth, The Taming of The Shrew and The Tempest, might have been lost forever.

During Shakespeare’s life, his individual plays were published only as quartos – flimsy pieces of printed paper folded into quarter-sized pamphlets and sold for sixpence.

Considered throwaway items at the time, they were not designed to last and, when Shakespeare died in 1616, there was a real likelihood the quartos, as well as the plays printed on them, would disappear forever.

Luckily, in 1623, seven years after his death, two of his colleagues and fellow actors, John Heminge and Henry Condell, decided to preserve their friend’s legacy by publishing a compendium of his works in one single and substantial 900-page volume. Eighteen of the plays are believed never to have been printed previously.

READ MORE: William Shakespeare painting could be only one in his lifetime

Entitled Mr William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories & Tragedies, 750 copies were printed which sold for between 15 and 20 shillings. Now known as The First Folio, only 235 copies survive, each worth millions.

The highest amount ever paid for one at auction was in October 2020, when an American collector, Stephan Loewentheil, spent $9.97m (£7.84m) at Christie’s auction house in New York.

The lion’s share of the 235 Folios are in libraries, colleges or private collections in the United States. More than a third – 82 to be precise – are looked after by the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC.

The rest are spread across the globe – several in Japan, and the odd copy in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India and Chile.

Luckily for us, around 50, though, still remain here in the UK. In celebration of the First Folio’s 400th anniversary this year, many of these are on public view around the country, in Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre and the British Library in London, for example, as well as Stratford-upon-Avon where the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust maintains three copies, including one belonging to the RSC.

Greg Doran is artistic director emeritus at the RSC and has been described as “one of the great Shakespeareans of his generation”. He has directed the likes of Judi Dench, Helen Mirren and David Tennant in Shakespeare roles – even King Charles III himself, who, in 2016, as the then Prince of Wales (not Denmark!), played Hamlet in Doran’s Shakespeare Live! production for the BBC.

The King and Queen host a reception for Shakespeare’s works (Image: Getty)

On his global travels, Doran has had the opportunity to inspect several of the remaining First Folios, which he has written about in his new book My Shakespeare: A Director’s Journey through the First Folio. He told the Express about some of the volumes and their owners he’d met, and in particular one lifelong Shakespeare fan, King Charles III, whose predecessors have been the subject of some of The Bard’s work: “I saw a copy at Windsor Castle which the King showed me,” he says.

“It’s a Folio owned by Charles I which he was reading at Carisbrooke Castle, where he was held captive, on the Isle of Wight, just before his execution. And I wondered: which play was he taking consolation from?

“Was he perhaps reading something pertinent like Richard II? He also ended up in prison before being killed, and famously says: ‘I wasted time and now doth time waste me’. But no, it seems that, actually, he was reading the comedies…which I suppose you would do, if you were in that position, to try and cheer yourself up!”

Doran explains how our current King was a loyal president of the RSC for over 30 years. “I’ve known of his passion for Shakespeare from the way he regularly comes to performances,” he says. “There’s always something that strikes him about the play that is unique to him and his position.

“For example, he noted that his predecessor Charles I had annotated his copy of the First Folio with his motto Dum spiro spero, which means: ‘While I breathe, I hope’.”

William Shakespeare’s Henry V at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre (Image: Getty)

The King confessed to Doran that he is also fond of making notes in the margins. “Whenever he comes to Stratford and wants to record a particular line from a play, he scribbles it down in his own Complete Works of Shakespeare which he was given for his 21st birthday.”

But not, Doran hastens to add, on the First Folio itself, thankfully.

The RSC director also inspected Folios in Germany, USA, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and Japan. “There’s also a copy in a university in Tokyo that belonged to a man called Paul Francis Webster, who was the only African American to own a copy,” he adds. “It turns out, he was the lyricist for the theme song for Spiderman. He also won an Oscar, in 1954, for a song in Calamity Jane.

“And that same copy which he owned had belonged, before, to the man who wrote the words to Handel’s Messiah, in 1741. It’s extraordinary that two lyricists, two centuries apart, should own that same copy.”

As well as the stories they contain, the remaining Folios give an insight into the lives of the owners who read them all those centuries ago. Professor Emma Smith teaches Shakespeare Studies at Hertford College, Oxford, and is author of The Making of Shakespeare’s First Folio.

She told the Express about some of the annotations she discovered in original volumes during her research: “There are many differences in the lives these 400-year-old books have had,” she says. “Some of them have doodles and marginalia in the sides; some of them have cat paw prints on them.”

In Oxford there’s one Folio that once belonged to a serious Shakespeare scholar in the 18th century called Edmond Malone, with a wine glass stain on it.

Smith adds: “It’s actually on Henry IV, Part 1, which is very appropriate because that’s a play all about taverns and indulgent living.”

Smith notes how the provenance and previous ownership of the Folios can be intriguing for modern scholars. “A hundred years ago, we would only have been interested in the most absolute perfect copies which look as though nobody has touched them,” she says. “Now we’re much more interested in the ways that people have left their mark upon this book: the names of the owners that people have written in them and the notes they have made.”

The cleanliness-obsessed Victorians even went so far as to bleach the pages of their Folios in order to eradicate the marginalia and doodles they considered untidy and undesirable; in complete contrast to the way historians approach their research today.

Shakespeare’s works continue to have relevance over four centuries after they were written, not just to scholars, actors and directors, but to everyday speakers of the English language. The plays are still widely performed globally. He is by far the most quoted writer in the history the English-speaking world, and is believed to have introduced or popularised over 1,700 words and phrases still in use today: ‘World is my oyster’, ‘Blinking idiot’, ‘Cruel to be kind’, ‘Wild goose chase’, ‘Clothes make the man’, ‘It’s Greek to me’, ‘All that glitters is not gold’.

A sign of his global popularity is that, over the centuries, his works have been translated into 80 or so different languages, including – rather bizarrely – the fictitious Klingon language from sci-fi series Star Trek.

If Shakespeare were alive today, he would no doubt be flattered… if a little baffled.

- The exhibition 400 Years of the First Folio is at Stratford-upon-Avon until November 5. Shakespeare.org.uk. The RSC’s production of Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet, London’s Garrick Theatre, from September 30. rsc.org.uk

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal