Hibernating bears can’t help us escape long plane flights or unforgiving winters — but they may help us prevent blood clots.

The bears, during hibernation, prevent blood clots in their own bodies by keeping a low level of a key protein in their blood, according to a new study published in Science.

Now, the researchers hope their findings can be applied to developing future medications in humans that can mimic the way nature prevents blood clots in bears.

BLOOD CLOT SYMPTOMS TO LOOK OUT FOR

The researchers compared blood samples from 13 wild brown bears during the winter while they were hibernating with blood samples during the summer when the bears were more active.

They specifically looked at platelets — which help the blood form clots — finding that the hibernating bears’ blood samples had platelets that were less likely to clump together than the samples taken of the bears during the summer.

A grizzly bear is shown foraging in Glacier National Park in Montana. While hibernating bears can’t help us escape long plane flights or unforgiving winters — they may help us prevent blood clots, according to a new study that looked at the blood samples of both hibernating bears and active bears. (iStock)

The research team also found that when the platelets did clot, they did so more slowly.

The study found that a key difference in the bears’ winter and summer blood samples were levels of a protein called heat shock protein 47 — or HSP47 — in platelets.

WHO IS AT RISK FOR DEVELOPING BLOOD CLOTS?

This protein is normally found in cells that form connective tissues like bone and cartilage, as well as platelets, where HSP47 attaches to a protein called collagen that helps them stick together to form a clot.

The study found a key difference in the bears’ winter and summer blood samples.

The hibernating bears had approximately one-fiftieth of the amount of HSP47 found in active animals.

The research was done by cardiologists at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, who teamed up with a Scandinavian team and other researchers to study hibernating brown bears in Sweden, according to Science.

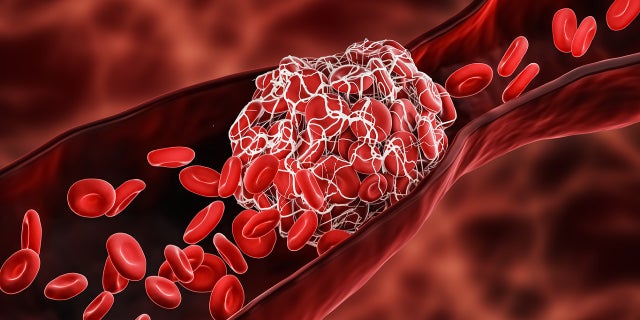

Blood consists of red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets that float in the liquid portion of the blood known as plasma. When we bleed, this initiates the coagulation — or clotting cascade — that activates proteins on platelets to clump to fill the hole in the blood vessel, so that we stop bleeding. (iStock)

The researchers also performed lab experiments with mice to confirm that HSP47 was the reason behind the hibernating bears’ lack of blood clots.

The mice that lacked the HSP47 protein had fewer clots and lower levels of inflammation compared to animals who had HSP47.

BE WELL: WHY IT’S WISE TO DITCH THE ELEVATOR AND TAKE THE STAIRS

In addition, researchers discovered that pigs that had recently given birth — animals that are quite immobile for up to 28 days while feeding their piglets — also had lower HSP47 levels compared with active pigs.

The findings also applied to people who have long-term immobility issues.

Pigs that had recently given birth — animals that remain quite immobile for up to 28 days while feeding their piglets — also had lower HSP47 levels, compared with active pigs, researchers found. (iStock)

People with spinal cord injuries also had low levels of HSP47. In addition, 12 healthy volunteers had lower HSP47 levels after 27 days of relative immobility in a bed-rest study.

How the body forms clots

“When we cut ourselves, we bleed because blood vessels under the skin tear,” Dr. Mikkael Sekeres, chief of the division of hematology at Sylvester Cancer Center in the University of Miami in Miami, Florida, told Fox News Digital. (He was not involved in the research.)

“They then release chemicals that, in turn, activate proteins in the plasma,” added Sekeres, author of the book “Drugs and the FDA: Safety, Efficacy, and the Public’s Trust.”

This process can sometimes get activated inappropriately even when there’s no bleeding — causing “deep vein thrombosis.”

Blood consists of red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets that float in the liquid portion of the blood known as plasma, according to Cleveland Clinic.

BLOOD DONATIONS THIS WINTER: AMERICAN RED CROSS URGES PEOPLE NOT TO FORGET TO DONATE

When we bleed, this initiates the coagulation — or clotting cascade — that activates proteins on platelets to clump to fill the hole in the blood vessel, so we stop bleeding, Sekeres explained.

Deep vein thrombosis can be dangerous

This process can still sometimes get activated inappropriately even when there’s no bleeding, causing “deep vein thrombosis,” or DVT.

Blood consists of red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets that float in the liquid portion of the blood known as plasma, according to Cleveland Clinic. When we bleed, this initiates the coagulation — or clotting cascade — that activates proteins on platelets to clump to fill the hole in the blood vessel so that we stop bleeding, one doctor explained. (iStock)

Common symptoms of DVT include swelling, pain, tenderness and redness of the skin in the lower leg, thigh, pelvis and sometimes even the arm, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Some 50% of people with DVT will not have any symptoms, the agency added.

People can often form in the large veins in the legs, “which can become life-threatening if they travel to vital organs like the lungs — termed [a pulmonary] embolism,” added Sekeres.

A “prolonged lack of activity” — such as during long plane flights — can cause the blood to pool and make people more at risk for DVTs.

A pulmonary embolism, which is the most serious complication of DVT, occurs when a part of the clot breaks off and travels through the bloodstream to the lungs, blocking vital blood flow, per the CDC.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

Sekeres noted that “prolonged lack of activity” — such as during long plane flights — can cause the blood to pool and make people more at risk for DVTs.

Other risk factors include certain medications, such as hormone therapies, surgery or “inherited defects in the clotting cascade that encourage it to ‘turn on,’” he added.

A commercial airliner cabin packed with passengers. Health experts advise that people get up and move around every so often on long flights. Other good advice includes stretching the feet and calves to help blood flow. (iStock)

The CDC advises that people see a doctor immediately if they have any symptoms of a DVT.

‘Potential target’ for DVT medication

Experts could help develop potential medications that would target HSP47 from attaching to proteins or immune cells that initiate clots, according to a report on the study’s key findings.

More research is needed to better understand how the human body specifically regulates HSP47.

“We prevent the development of DVTs with medications that block segments of the coagulation cascade, or that interfere with proteins on platelets, preventing the clot from forming,” Sekeres added.

“The protein HSP47 could be a potential target for one of these medications.”

Most animals use the same proteins to not only make clots but to prevent blood loss.

Yet the sequence of events leading to forming a clot may vary among species, according to Science News, an independent journal that reports on the latest science.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

More research is needed to better understand how the human body specifically regulates HSP47 — and how being motionlessness over time motivates the body to make less HSP47, Science News added.

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal