William VanWhy says he was feeling emotionally overwhelmed when he checked himself into the mental health unit at Northwest Medical Center in Arkansas last year. Four days later, he was still in the locked unit but desperate to leave.

“I was not receiving any medical care at all,” VanWhy, 32, said.

Mental health patients in Arkansas can be held against their will for 72 hours if they are deemed a danger to themselves or others. But to keep them any longer than that, a medical provider must file a court petition and get the consent of a judge.

No petition was filed in VanWhy’s case, and his partner, with the help of a lawyer, ultimately succeeded in getting a court order for his release.

A few hours later, a sheriff’s deputy walked into the hospital with the order in his hand and VanWhy’s husband at his side. In the elevator, they bumped into a nurse from his unit.

“I’m glad he’s getting out,” the nurse said, according to bodycam footage obtained by NBC News. “Don’t repeat that.”

VanWhy was released about 20 minutes later. “Oh my gosh. You saved my life,” he told the deputy, the bodycam footage shows.

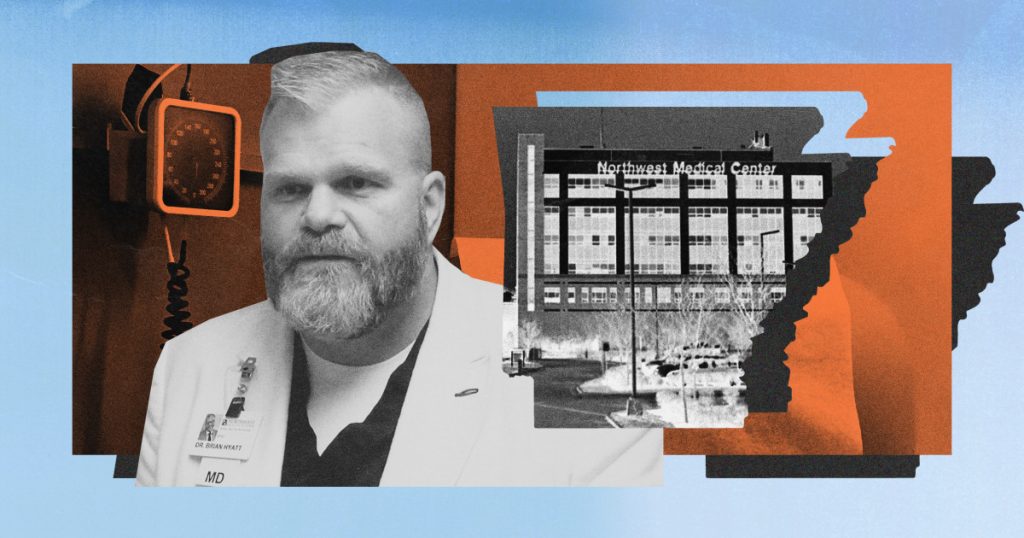

The man who led the unit at the time, Dr. Brian Hyatt, was one of the most prominent psychiatrists in Arkansas and the chairman of the board that disciplines physicians. But he’s now under investigation by state and federal authorities who are probing allegations ranging from Medicaid fraud to false imprisonment.

VanWhy’s release marked the second time in two months that a patient was released from Hyatt’s unit only after a sheriff’s deputy showed up with a court order, according to court records.

“I think that they were running a scheme to hold people as long as possible, to bill their insurance as long as possible before kicking them out the door, and then filling the bed with someone else,” said Aaron Cash, a lawyer who represents VanWhy.

VanWhy and at least 25 other former patients have sued Hyatt, alleging that they were held against their will in his unit for days and sometimes weeks. And Arkansas Attorney General Tim Griffin’s office has accused Hyatt of running an insurance scam, claiming to treat patients he rarely saw and then billing Medicaid at “the highest severity code on every patient,” according to a search warrant affidavit.

As the lawsuits piled up, Hyatt remained chairman of the Arkansas State Medical Board. But he resigned from the board in late May after Drug Enforcement Administration agents executed a search warrant at his private practice.

“I am not resigning because of any wrongdoing on my part but so that the Board may continue its important work without delay or distraction,” he wrote in a letter. “I will continue to defend myself in the proper forum against the false allegations being made against me.”

Northwest Medical Center in Springdale “abruptly terminated” Hyatt’s contract in May 2022, according to the attorney general’s search warrant affidavit.

In April, the hospital agreed to pay $1.1 million in a settlement with the Arkansas Attorney General’s Office. Northwest Medical Center could not provide sufficient documentation that justified the hospitalization of 246 patients who were held in Hyatt’s unit, according to the attorney general’s office.

As part of the settlement, the hospital denied any wrongdoing.

“We believe hospital personnel complied in all respects with Arkansas law, which heavily relies on the treating physician’s assessment of the patient, including in decisions related to involuntary commitment,” Aimee Morell, a Northwest Health spokeswoman, said in a statement.

“While it is not our practice to comment on pending litigation matters, I can share that last spring, we undertook a number of actions to ensure our patients’ safety, including hiring new providers responsible for the clinical care of our behavioral health patients in early May 2022,” Morrell added.

Hyatt, 50, has not been charged with a crime. Neither he nor his lawyer responded to multiple requests for comment.

But his legal team provided a statement to Arkansas Business last month.

“Dr. Hyatt continues to maintain his innocence and denies the allegations made against him,” the statement said in part. “Despite his career as an outstanding clinician, Dr. Hyatt has become the target of a vicious, orchestrated attack on his character and service. He looks forward to defending himself in court.”

Arkansas Attorney General Tim Griffin declined to comment. “We have no additional details to provide at this time,” he said.

Charlie Robbins, a spokesman for the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Western District of Arkansas, said the execution of a search warrant is “an important step in any lengthy, ongoing investigation.

“In light of the fact that this investigation is still ongoing, we will not be making any additional comments,” he said.

Massive Medicaid payouts

A graduate of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Hyatt was named the medical director of Northwest Medical Center’s behavioral health unit in Jan. 2018.

The number of beds expanded from 25 to 75, and the claims to Medicaid and Medicare, as well as to private insurance, surged, according to the Arkansas attorney general’s search warrant affidavit.

Hyatt was getting paid $1,367 per day, according to a report prepared by the Arkansas attorney general’s office. And at the same time he was also running his own private practice, Pinnacle Premier Psychiatry, in the town of Rogers about 25 miles away, according to the attorney general’s office.

The claims he submitted indicated that he conducted daily face-to-face evaluations with patients at the hospital.

But a former staffer came forward in April 2022 and told state investigators that Hyatt was only on the floor with patients “a few minutes each day and that Dr. Hyatt had no contact with patients,” the affidavit says.

Investigators reviewed 45 days of surveillance footage from the facility and concluded that Hyatt entered a patient’s room or interacted with a patient only 17 times — for less than 10 minutes in total, according to the report prepared by the attorney general.

“Dr. Hyatt never had even a single conversation with the vast majority of patients under his care,” the affidavit says.

Shannon Williams, 52, says she was one such patient.

Williams, a nurse from Harrison, was grappling with the death of her grandmother when she learned that her brother had died from Covid while overseas. The news pushed Williams, who herself worked in a Covid unit, into what she described as “crisis mode.”

She ended up in the emergency room of a hospital about 90 minutes away from Springdale in February 2021. The next morning, she was transferred to Hyatt’s unit after a physician determined that she was a danger to herself, according to medical records. (Williams maintains that she was not suicidal.)

Upon arriving at the unit, Williams said she was stripped down and injected with a sedative against her will.

“I was terrified,” Williams said.

She was held for five days, according to her medical records, despite, she says, her requests to leave.

“It was as if I was in a prison,” Williams, a mother of three, said. “It was like a nightmare. If I cried, then I was again threatened with more time.”

According to the search warrant affidavit, Hyatt’s Medicaid claims dwarfed those of other psychiatrists in Arkansas.

From January 2019 to June 2022, Medicaid paid out more than $800,000 to Hyatt’s facility.

“Dr. Hyatt is a clear outlier, and his claims are so high they skew the averages on certain codes for the entire Medicaid program in Arkansas,” the affidavit says.

Medicaid uses a coding system to determine how much to pay providers — with the highest codes billing at the highest rates because those patients require more care.

It’s common for a newly admitted patient to come in at the highest severity code, which suggests the person is unstable and dealing with a serious issue, and then progress to a lower code before being released.

But 99.95% of Hyatt’s Medicaid claims came in at the most expensive code, the affidavit says.

“According to the claims submitted by Dr. Hyatt and the non-physician providers working under his supervision, no patient being treated in the behavioral unit located at Northwest Medical Center ever got better, at least not before the day of the patient’s release,” the affidavit says.

Mocking emails

Before he came to represent VanWhy, Cash had a bizarre interaction with Hyatt over a different patient.

In January 2022, Cash sent the hospital a fax demanding the immediate release of his client, a patient named Karla Adrian-Caceres.

Adrian-Caceres had arrived at the unit the day before and was clamoring to leave, according to a lawsuit she filed in January 2023.

Adrian-Caceres’ mother went to the hospital to pick her up but was told her daughter would not be released, the lawsuit says. The following morning, Hyatt responded by email to Cash, saying he would neither confirm nor deny that Adrian-Caceres was in his unit.

“Our facility is in receipt of your silly demands and libelous commentary regarding someone you claim to represent who is purportedly within our facility,” Hyatt said in the email, which was included in Adrian-Caceres’ court filing.

Hyatt said he would only check to see if she was there if Cash got his client to sign a “release of information form.”

Cash responded four hours later with a court order demanding Adrian-Caceres’ release.

Cash gave the court order to Adrian-Caceres’ mother, and she brought it to the hospital, but the hospital still refused to release her daughter.

So Cash got a second court order, and the judge ordered the sheriff’s office to enforce it, according to her lawsuit.

A deputy went to the facility with Adrian-Caceres’ mother and secured her release, according to documentation from the sheriff’s office obtained by NBC News.

The next morning, Hyatt emailed Cash, mocking the colleges he attended.

“I guess this is what they teach at Poteau Junior College…sorry…Carl Albert State and Northeastern State University,” Hyatt said in the email.

He directed Cash to contact his attorney. “You won’t find him in your “college’s” yearbook,” he wrote.

When Cash heard from VanWhy’s husband two months later, he didn’t bother trying to get the patient released on his own.

“I went straight to the sheriff this time,” Cash said.

Cash said the patients he spoke to were adamant that they received virtually no care while they were being held in Hyatt’s unit. These were people who were vulnerable and oftentimes in need of serious support or therapy, he said.

“Some of them did need help,” Cash said. “And what they got was hurt.”

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal