Thousands more Americans are now testing positive each year for alpha-gal syndrome — a condition spread by tick bites that causes allergic reactions to eating red meat. New data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows up to 450,000 people in the U.S. have been affected since 2010.

These figures mark a steep increase in cases since alpha-gal syndrome was first reported among a handful of Virginians in 2008 after being bitten by ticks.

Many cases are also likely going undiagnosed, the CDC now says, citing “concerning” knowledge gaps found in a separate study among American doctors surveyed about the red meat allergy.

“The burden of alpha-gal syndrome in the United States could be substantial given the large percentage of cases suspected to be going undiagnosed due to non-specific and inconsistent symptoms, challenges seeking healthcare, and lack of clinician awareness,” the CDC’s Dr. Johanna Salzer said in a release.

Salzer is a senior author on the two new papers, which were published Thursday in the agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In one study, researchers looked at data from Eurofins Viracor, the lab responsible “for nearly all testing in the United States before 2022” of suspected alpha-gal cases. Outside of a handful of academic or specialty clinics, the CDC says other commercial labs did not begin offering alpha-gal testing until 2021.

Positive blood tests for alpha-gal syndrome generally climbed each year from 13,371 in 2017 to 18,885 in 2021, aside from a dip during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

While false positives are possible, CDC says separate unpublished surveillance data from New Jersey suggests around 90% of people who test positive had clinical symptoms consistent with the red meat allergy.

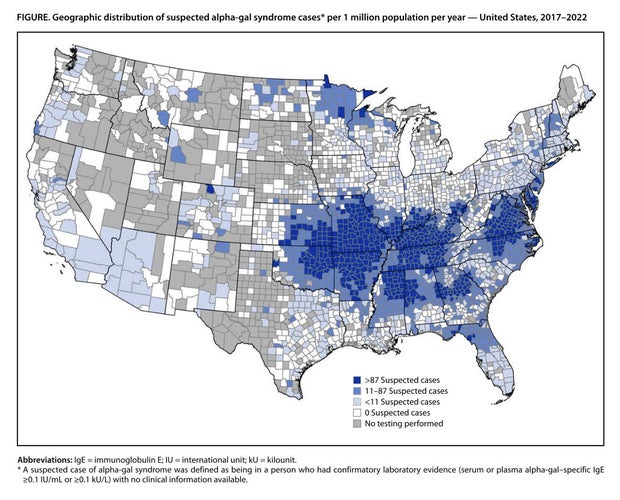

Most cases were identified in southern and eastern states known to harbor the lone star tick, whose saliva is linked to the allergy. Lone star ticks have been spotted across a broad swath of the country, from Texas through Maine.

CDC

However, positive tests also found clusters of cases in residents of counties in Minnesota and Wisconsin, where lone star ticks are not known to be living. Other kinds of ticks outside the U.S. have also been linked to alpha-gal syndrome.

“[C]ases outside the established range of this tick species need to be further investigated to better understand exposure history and contributing factors associated with the onset of this allergic condition,” the study’s authors wrote.

A separate study surveying a panel of 1,500 primary care doctors, pediatricians, physician assistants and nurses found 42% had never heard of the syndrome, with another 35% saying they were “not too confident” in their ability to diagnose or manage patients who have it.

“The lack of [health care provider] knowledge of [alpha-gal syndrome] is likely to lead to under testing, further hampering knowledge of the national prevalence,” that study’s authors wrote of their findings.

Combined with the survey findings, as well as previous testing results collected through 2018, the CDC estimates that up to 450,000 people in the U.S. may have been affected by alpha-gal syndrome since 2010.

“If testing trends continue, and the geographic range of the lone star tick continues to expand, the number of AGS cases in the United States is predicted to increase during the coming years,” the authors wrote.

What is alpha-gal syndrome?

Alpha-gal syndrome refers specifically to an allergic reaction against a sugar molecule that scientists call oligosaccharide galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose — nicknamed alpha-gal — that is found in many foods made from mammals.

The list of foods that can contain alpha-gal includes red meat, like beef, pork or lamb, especially in cuts of organ meat like liver.

Many patients are still able to eat products like milk or cheese, though some may also need to cut these dairy products too in order to avoid symptoms.

Other products derived from animals, like gelatin, can contain alpha-gal and in rare cases cause reactions to some vaccines or capsules used in medication.

Allergic reactions typically appear from two to six hours after exposure to alpha-gal, the CDC says, and can range from mild symptoms like rashes and nausea to life-threatening anaphylaxis.

Reactions to the cancer drug cetuximab, an antibody treatment, triggered early clues to the growing prevalence of the allergy in specific parts of the country where the tick bites were more common. (Unlike some other antibody drugs, cetuximab is produced using a cell line that expresses the gene for the alpha-gal molecule.)

While bites from the lone star tick are the main risk factor for Americans in developing the allergy, scientists say more research is still needed into understanding how the saliva of the lone star ticks leads to the allergy in some who are bitten.

A panel of federal advisers in 2019 called for ramping up research into treatments for the allergy, which is currently incurable and is managed largely with experimental or so-called “off-label” options not formally approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

“Alpha-gal syndrome is an important emerging public health problem, with potentially severe health impacts that can last a lifetime for some patients,” the CDC’s Dr. Ann Carpenter, a lead author of one of the papers, said in a release.

The agency urges Americans to take steps to avoid tick bites — which can cause a range of different illnesses — especially during warmer months of the year.

That includes using insect repellents and avoiding heavily wooded or bushy areas where the bugs come into contact with people or their pets.

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal