PAST MASTER: Dame Mary at the Colosseum in Rome (Image: PA)

Bear with me, but how often do you think about Ancient Rome? I’m only asking because this slightly bizarre question has been doing the rounds on social media after a flurry of viral Tik-Tok videos of women quizzing husbands or partners. And the answer from the average bloke? A lot more than you might think, it turns out. “Every day”, or at least “several times a week”, are among common responses.

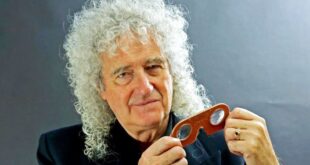

Mary Beard laughs when I suggest she’s in some small way responsible for the current craze for all things Roman. She is, after all, our most famous classical historian, a star of radio and television, whose 2015 book SPQR: A History Of Ancient Rome was both critically and commercially acclaimed and sold by the situla-load (that’s Latin for bucket). Frankly, there’s no need to ask her how much she thinks about the Romans: a lot, if her brilliant new book, Emperor Of Rome, which examines the men – yes, it was always men – who ruled the Roman Empire, is anything to go by.

It’s a wonderful mosaic of detail, sometimes from the most unusual of sources including graffiti, memos and bills, that builds a glorious picture of the role of emperor.

But it’s the mere tip of the gladius (Latin for the swords carried by Roman foot soldiers) when it comes to the ancient world’s domination of popular culture.

From the oft-repeated Seventies TV drama, I, Claudius, to Latin-spraffing politicians and constant documentaries and films about gladiators, the Roman Empire’s in rude health – despite having collapsed in ignominy some 1,500 years ago.

Even Latin, that famously “dead” lingo, is now the fourth most studied language in British primary schools behind French, German and Spanish.

“We’re keener on gladiators than the Romans were,” she smiles.

But as Beard, 68, tells me from the kitchen of her comfy book-lined Cambridge home, her latest work is an attempt to demystify the Roman emperors. They weren’t all the psychopaths and murderers they’ve been portrayed as, even in their own day.

READ MORE: What lies behind Stephen King’s scary influence on the world of horror?

Russell Crowe as Roman commander Maximus in Gladiator (2000) (Image: Getty)

Take Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus – better known as Caligula (37-41AD) – who infamously planned to make his horse a Consul, so we’re told.

He was described as insane, short-tempered and self-absorbed. But hang on, says Beard, could these stories have been inventions of the Romans themselves?

“Why has Caligula gone down in history as a psychopath? Well, partly because he was assassinated. And once he was dead, there was a new broom, and everybody was dumping on the previous emperor. It was a chorus of ‘I thought he was terrible’,” she explains.

“And that goes on throughout history. Sometimes people really are monstrous and then they’re assassinated. Other times, they’re not particularly monstrous, but there’s a palace coup and they get recreated as monsters because it’s in everybody’s interests they should be remembered that way.

“I wanted to take a bit of a different view: Here you’ve got the ruler of the biggest empire the West has ever seen. How the hell does he do it? When he gets up in the morning, what does he do? What does he eat, where does he go? Who does his paperwork?

“Now some of this means that I’m not so hooked on the blood-stained corridors of power because I’m more interested in thinking about what it was really like to be an emperor.”

Don’t worry, however, if you don’t know your Caesar from your Augustus. It doesn’t matter. “People might think, ‘Oh, God, I don’t know whether Claudius came before Caligula. I can’t tell Marcus Aurelius from Antonius Pius. Is that going to be a problem with this book?’

“Actually, no. Outside of a small circle in Rome, most Romans probably didn’t know. There’s a lovely papyrus scrap from Roman Egypt and it’s a guy with very good handwriting trying to make a list of all the Roman emperors… and he gets it wrong.” Marcus Aurelius (161-180AD) remains one of the most famous emperors of the second century. His series of personal Meditations is a modern bestseller.

“At one point, he looks back over his predecessors and says, in Roman terms, it was the ‘same play, different cast’,” says Beard.

“That’s my book in a nutshell. They all lived in the palace, they all went on some kind of military campaign, they travelled, they had sex. They did their paperwork, they answered petitions.” So why do we remain so utterly fascinated by them?

- Advert-free experience without interruptions.

- Rocket-fast speedy loading pages.

- Exclusive & Unlimited access to all our content.

“Partly it’s because they are us writ large,” she continues. “They are the blueprint for the modern world but in a more extravagant, larger-than-life way.

“They are more lascivious, more corrupt, more imperialist. They’ve also formed a kind of template of power and what it looks like since the ancient world. So I think we’re curious about how they did it, even if we disapprove of some of their behaviour.”

Brian Blessed, left, as Gaius Octavian, and Ian Ogilvy as Drusus, in 1970s TV drama, I, Claudius (Image: Getty)

Does Beard see a comparison between the growing gap between haves and have-nots in contemporary society and the Romans? She cites “imperial” modern rulers like the late Silvio Berlusconi, former Italian prime minister, and shoe-mad Imelda Marcos of the Philippines. “Elagabalas [218-222AD] never wore the same pair of shoes twice. He was so rich. When we imagine what it is to be all powerful, we often focus on footwear.

“There’s a wonderful story, about a would-be emperor, when the grandfather of one ancient writer manages to get into the palace kitchens of Antony and Cleopatra. He sees eight boars roasting and he says, ‘Big dinner?’ And is told: ‘No, it’s a small group, but we don’t know when they want to eat’. That’s what was said about Prince Charles, always denied by the Palace, that he had seven eggs boiled one after the other so one would be perfect when he was ready to eat.”

Like such modern tales of the rich and famous, there’s no point getting too hung up on whether they are true or not, she insists. They’re useful as metaphors.

Beard admits that looking afresh at the emperors has given her a certain amount of sympathy for them and their ilk, right up to modern politicians.

It was, after all, a risky job.

“You wouldn’t have wanted it,” she smiles. “When the emperor Domitian [81-96AD] was assassinated at the end of the first century, the conspirators tried in advance to find someone to take over and actually had a couple of refusals.”

Then there was Claudius (41-54AD), said to have been discovered cowering behind the palace curtains following the murder of his predecessor, his nephew Caligula.

“In whose interest was that told I wonder?” muses Beard, who retired last year after a 40-year career at the University of Cambridge. “Well, it was probably in Claudius’ interest, wasn’t it? ‘I wasn’t involved in the killing. Not me, Guv. I had nothing to do with it. I was just the choice of the army’.

“We like to think that if we were living under an autocrat, we would be freedom fighters. No, we wouldn’t, we’d probably be keeping our heads down and going along with it. And what’s striking about one-man rule of imperial power in Rome is that there’s almost no opposition to the system. It flickers when Caligula is killed. But after that, there’s no trace of someone saying, ‘There shouldn’t be an emperor’. What keeps autocracies in power is not the murder and the violence. It’s the fact people go along with it.

Roman emperor Caligula (Image: Getty)

“In the course of writing this book, I came to hate the idea of dictatorship or emperorship more, but I did start to feel a little bit more sympathetic to the poor bugger who was emperor. It’s a prison for him as much as a palace. And no one’s ever going to tell him the truth. He can’t trust anybody.”

Rolling forward to the present day, I wonder if it’s given her a smidgen of sympathy for the likes of Vladimir Putin or North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un?

“It doesn’t make you like them, but it makes you see they’re caught in the system too. Now, they’re in a much better place than most people. But when you get that kind of autocratic rule, everybody is involved in not telling the truth. And what I think the Romans are saying in some of these anecdotes is that autocracy is a mad, dystopian world in which nothing is as it seems.

“It takes away your ability to judge with your own eyes. I don’t know what an encounter between Putin and one of his advisors looks like, none of us do. But there must be a sense of, what do you say and what can you believe.”

And despite the popularity of the ancient world, there’s an irony in the fact that the rise of STEM subjects like physics, maths and computing, has put the humanities on the backfoot in higher education. “There aren’t very many people who say humanities are a bad idea,” says Beard. “But there is a sense that they’re not essential, right? It’s very nice to have a culture in which some people read Latin. But if you’re short of money, we’re not going to pay for it.

“That rests on the idea STEM subjects are essential, that society would collapse without them. Whereas humanities are kind of a nice added extra. But humanities teach you to be a democratic citizen, you learn how to make decisions on the basis of inadequate evidence.

“That doesn’t mean everybody has to learn Latin and Greek – I’m very happy when people do – but these subjects are absolutely essential for the wellbeing of the body politic.

“It’s no good saying that if we all became computer engineers, the country would be more prosperous. It would just be different.”

She continues: “The humanities have got to speak for themselves and say, ‘There’s a purpose here. And the purpose of education is not just to make a large salary’.”

Surely the fact a recent Prime Minister is well known for his love of the classics should help, shouldn’t it? Beard is not quite so sure.

“The trouble is it has kind of fixed the idea of classics in peoples’ minds as being something you do at Eton,” she says carefully. “One of my life’s projects has been to say Latin isn’t just for the posh. Now I don’t want to stop the posh doing it. I’m a broad church kind of woman.

“But when you hear Boris Johnson on the radio, spouting a bit of Latin, or more often Greek, in a posh accent, you do wonder if that sends a signal to ordinary kids that classics isn’t really for people like them?”

● Emperor Of Rome by Mary Beard (Profile, £30) is available to order from Express Bookshop. For free UK P&P, visit expressbookshop.com or call Express Bookshop on 020 3176 3832

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal