Annemarie Gibson’s son Owen was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in 2011. Six years later, in 2017, her other son Thomas got the same diagnosis.

The San Diego mother, 49, has health insurance. Each month, she says, she pays $400 in premiums for her family. But that doesn’t cover the cost of insulin for her sons, both now in their teens. That medication is another $200 out of pocket.

Gibson is among the millions of people in the United States who won’t see relief when the Inflation Reduction Act goes into effect on Jan. 1, capping the monthly out-of-pocket cost of insulin at $35 for seniors on Medicare. In August, Republicans successfully blocked a provision in the bill that would have capped the out-of-pocket cost of the drug for everyone on private insurance.

“It doesn’t seem fair,” Gibson said of the cost of the drug needed to keep her children alive. “We don’t have other options. We don’t have another choice.”

More than half of the diabetics in the U.S. — over 21 million people — are under age 65, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nearly 16 million people ages 65 and up have diabetes, though not all of them are on Medicare.

If the cost of the drug becomes untenable, some people try to ration their insulin — a choice that can lead to hospitalization or death. For others, the cost of the drug exerts its own chronic financial pain.

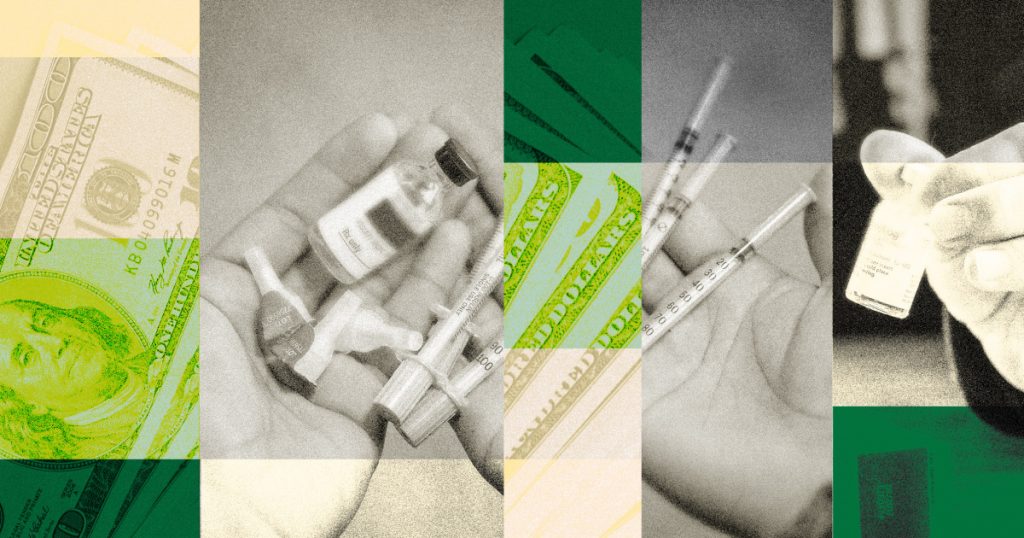

How much does insulin cost?

Pinning down the cost of a vial of insulin is extremely difficult; what an individual will pay depends on a number of factors, including what type of insulin they are using, insurance status and whether they’re eligible for a rebate from the drugmaker.

It’s clear that cost of insulin in the U.S. is far higher than in other countries. The RAND Corporation, a public policy think tank, estimated that in 2018, the average list price for one vial of insulin in the U.S. was $98.70 — up to 10 times more than other countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a Paris-based research group. Even when the analysts accounted for rebates offered by drugmakers, the cost of insulin was still four times higher than other countries.

People with Type 1 diabetes need, on average, one to three vials of insulin per month, according to the American Diabetes Association. Patients with Type 2 diabetes don’t always need to take insulin, but those who do can sometimes require more than people with Type 1 diabetes.

A report published in 2020 in JAMA Network Open found that in 2017, the average monthly out-of-pocket cost for insulin for people with a high-deductible insurance plan was $141. High-deductible plans usually have lower monthly premiums, but require the insured to pay much more out-of-pocket before coverage kicks in.

More than 50% of insulin users with employer-based insurance spent over $35 out-of-pocket on average for a 30-day supply of insulin in 2019 and 2020, according to the Health Care Cost Institute, a nonprofit group that tracks drug prices. About 5% of them spent more than $200.

Some people may pay even more.

Dr. Adam Gaffney, a critical care physician at the Cambridge Health Alliance in Massachusetts, said that even this year, he’s had patients who have spent $1,000 or more each month on insulin.

The Inflation Reduction Act is “useful, but it’s definitely not enough,” Gaffney said. For many people with diabetes, there is no substitute for insulin and there are no days off for them in taking the medication. “It is a unique medication in that way, and we should make it universally available,” he said.

High costs, high risks

The high cost of insulin has forced many people to ration the medication: Over 1 million people in the U.S. either skipped, delayed or used less insulin than was needed in the past year to save money, according to a study published in October in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine.

Rationing can have dire consequences.

Hattie Salzman, 25, of Kansas City, Missouri, experienced those consequences five years ago.

She was enrolled in a high-deductible plan and was paying around $550 a month for the insulin she needs to keep Type 1 diabetes under control. She couldn’t afford it. After months of rationing her medication, she said, Salzman ended up in the emergency room where doctors told her she was at risk for diabetic ketoacidosis, a life-threatening condition that occurs when too much sugar stays in the bloodstream because of a lack of insulin.

Salzman no longer rations the drug, and while she now has better health care coverage, she said she is still paying around $125 for a three-month supply of insulin.

“It’s just really frustrating,” said Salzman, who advocates for affordable insulin. “It makes no sense that we were so close to getting some help and then it was taken away.”

Even people with what’s considered good health insurance coverage can face steep costs in certain situations.

Chicago resident Anita Brown, 41, has Type 1 diabetes and said she pays around $60 to $70 for a three-month supply of insulin.

But about three years ago, someone stole her newly refilled supply of insulin from her purse while she was at a practice with her bowling league.

At the pharmacy, Brown was initially told that her insurance wouldn’t cover a replacement, and she would have to pay more than $1,000 for three vials.

“I’m running low on one of my bottles and I need this prescription,” she said of her thinking at the time. “I’m trying to figure out everything possible.”

In the end, Brown’s insurance allowed her to initiate emergency coverage, so she could refill her prescription for $60. But it’s a benefit that can be used only once a year.

“I have insurance. I’m supposed to be OK with it, but it’s still expensive for me,” she said. “What’s going on here?”

The path ahead

With Republicans taking control of the House next week, passing bipartisan drug pricing legislation that would cap the cost of insulin for people under 65 may prove difficult, said Juliette Cubanski, deputy director of the program on Medicare policy at KFF, formerly known as the Kaiser Family Foundation.

“I don’t think policymakers have landed on what to do,” she said.

It may be up to states and other entities to make up for what the Inflation Reduction Act fails to provide patients who need insulin, said Eric Tichy, division chair of pharmacy supply solutions for the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

States can also enact legislation that would make insulin easier to afford in emergencies.

In 2020, Minnesota passed the Alec Smith Insulin Affordability Act, which provides an emergency 30-day supply of insulin to patients for $35. The legislation is named after a 26-year-old man in Minnesota who was uninsured and died after rationing his insulin.

Gibson, the San Diego mother, said she just feels fortunate she has insurance and is able to cover the cost of her children’s medication each month. But she said worries about when her kids become adults and are no longer allowed on her insurance.

“There will be pressure for my kids to always have full-time jobs that offer employer-sponsored health care,” she said. “It won’t be easy if our kids end up off of our policy and are looking for a job.”

She said it still feels like her family is getting taken advantage of. In addition to insulin and insurance premiums, Gibson also must spend $550 every three months for glucose monitors and $1,100 for insulin pumps.

“I’m so angry,” she said. “It’s exhausting.”

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal