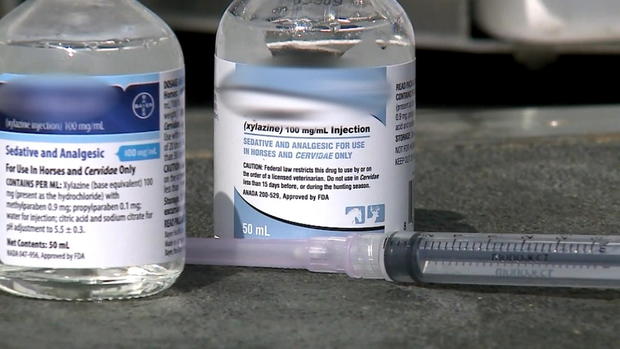

Xylazine, the animal tranquilizer that has been found mixed with opioids in most of the United States, will soon be be classified as a controlled substance in Pennsylvania.

It will be a Schedule III drug, meaning that it is considered a substance with a “moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence,” the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) says on its website. The decision allows law enforcement to prosecute people for illegally possessing and selling the drug, but Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro said that veterinarians will still be able to access it for work reasons.

According to Shapiro, the decision to schedule the drug will allow the state to require tighter record keeping and have the drug be stored in secure facilities, to limit theft and diversion. Manufacturers will also have to add additional checks to verify the person who ordered the drug is the one receiving it, and confirm that that person is authorized to receive the substance.

“Xylazine is a powerful animal sedative that should never be ingested by humans and is compounding our fight against the opioid crisis – and today, my administration is taking action to keep it out of our communities and protect Pennsylvanians. The steps we are taking today will help ensure this dangerous drug can’t be diverted from legitimate sources to the drug dealers harming our communities, while preserving its important use on animals,” said Shapiro in a press conference in Kensington, a neighborhood of Philadelphia.

A notice of intent has been submitted to schedule xylazine in the state. The final decision will be made in about a month, according to the governor’s office.

Pennsylvania is not the first state to classify xylazine as a controlled substance. In March 2023, Ohio authorized an emergency classification of it as a Schedule III drug. In 2018, Florida classified xylazine as a Schedule I drug, meaning that it is a crime to possess it or sell it in the state because it has no medically approved uses in humans. In late March, a bipartisan group of Congressional lawmakers introduced the Combating Illicit Xylazine Act, which would classify the drug as a Schedule III substance nationwide.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania’s largest city, has been widely considered the epicenter of xylazine use in the United States. Researchers told CBS News in March that the practice of mixing opioids with xylazine appears to have started in Puerto Rico, and has been happening in the United States since about 2008.

Since then, its prevalence has only increased: The DEA said in March that the combination of xylazine and opioids, also known as tranq, has been found in 48 of 50 states and said that about a quarter of powdered fentanyl tested by the agency contained xylazine. In 2021, the city of Philadelphia said that about 90% of opioid samples tested contained xylazine.

In April, the White House’s Office of National Drug Control Policy called the drug an “emerging threat” and requested $11 million to develop a strategy to tackle xylazine’s spread. Part of that strategy will be looking into whether Congress should classify the drug as a controlled substance.

While xylazine has been found in an increasing number of fatal overdoses, it’s not clear how responsible it is for those overdoses, because it’s used in conjunction with strong opioids like fentanyl and heroin, which can stop breathing. Xylazine can cause gruesome skin wounds and leave people in a vulnerable state if they are sedated in public.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were more than 107,000 opioid deaths between August 2021 and August 2022. About two-thirds of those deaths involved fentanyl, the DEA said. According to the DEA, about 3,000 overdose deaths involved xylazine.

“It is difficult to know which substance contributes most to fatality when an individual has more than one substance in their body at the time they died,” Jose Benitez, the lead executive officer of Philadelphia-based harm reduction organization Prevention Point, previously told CBS News.

Xylazine does not respond to naloxone because it is a sedative, not an opioid, and so the reversal agent is not formulated to work on it. Experts do recommend bystanders give a dose of naloxone to anyone who appears to be overdosing, because opioids are far more likely to be the cause of an overdose than xylazine.

Claire Zagorski, a chemist, paramedic and translational scientist in Austin, Texas, who studies xylazine, said she was wary of the decision to schedule the drug, because there are many questions surrounding the substance and its effects on humans. Classifying xylazine as a controlled substance could make it harder for researchers to study it.

“One thing we’ve seen a few times is that scheduling substances often has really frustrating, unintended consequences and often doesn’t work as well as we hoped it would,” Zagorski said. “One of the things that scheduling does is it makes it harder for us to research things because then we have to start going through a lot of permissions and processes in order to get a hold of a drug to test it. There’s a lot we need to figure out about xylazine’s action in humans that we don’t know, and we need to research … We don’t know what’s going on.”

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal