Does it ever seem like something is going on with our attention spans? The world’s #1 most downloaded app is TikTok, an infinite stream of very short video clips. Newspaper articles are getting shorter, and they tell you how much time you’ll need to read them.

And the average length of a shot in a movie is now under five seconds.

These days, multi-tasking while you’re tasking is the norm among young people. Just ask counselor Lauren Barnett and her daughters, Zoe and Sasha.

“We’re always holding another device,” said Sasha. “If you’re watching something, I feel like everyone always has their phone next to them.”

Zoe said, “My roommates would all be doing work on their computers, watching TV, but also on their phones texting people.”

Sasha admitted to having a short attention span: “Yeah. I can’t sit in long classes.”

Pogue asked, “Is there any cell in your body that’s like, ‘As soon as this is over, I’m gonna go right over and [get my phone]’?”

“Every cell!” laughed Barnett.

CBS News

Gloria Mark, an attention researcher at the University of California, Irvine, is author of “Attention Span: A Groundbreaking Way to Restore Balance, Happiness and Productivity” (Hanover Square Press). She says there is scientific evidence attention spans are getting shorter.

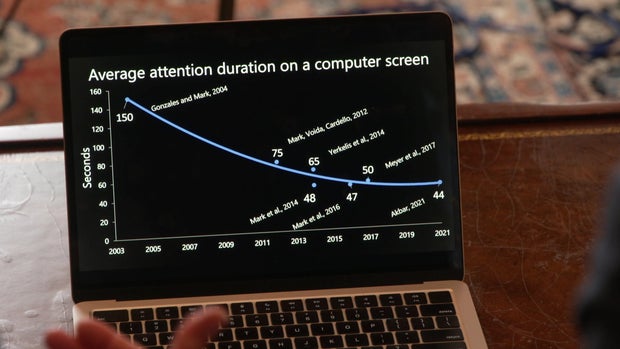

“We started studying attention span length over 20 years ago,” Mark said. “We would shadow people with a stopwatch, and every time they shifted attention, we’d click, ‘Stop’ In 2003, we found that attention spans averaged about two-and-a-half minutes on any screen before people switched. In the last five, six years, they’re averaging 47 seconds on a screen.”

And how can someone get anything done if you’re supposed to write a report, and 47 seconds later you’re switching to another app? “You do it with great difficulty,” she said.

CBS News

Mark maintains that a shorter attention span has three downsides: “The first is that people make more errors when they do attention shifting; second downside is that it takes longer to do something, ’cause we have to reorient to every new task every time we shift; the third downside — maybe this is the worst of all — is that stress increases. When people are working on multiple tasks and they have to shift their attention, their blood pressure rises.”

You don’t have to be a professor to guess at the cause of our greater distractability: It’s technology, of course … phones, social media, texting. Sasha Barnett can attest to that.

Asked to go into her iPhone’s Screen Time settings to see how many unlocks she had the day before, she was shocked to find she had 236 pickups. “That’s a lot!” she laughed.

So, is that it? Have we become overstimulated zombies? Cornell psychology professor emeritus James Cutting doesn’t think it’s time to abandon all hope. “I don’t think our attention spans have changed really at all,” he said. “There’s no data for that.

“I would point out that TSA baggage scanners work two-hour shifts, and that’s pretty intensive work for two hours. And many of us have watched teenagers play their games for many hours at a time. It strikes me that that kind of attention span is pretty impressive.”

But what about that business of movies shots getting shorter? We’ve come a long way from the pacing of “2001: A Space Odyssey” in 1968 … to last year’s “Top Gun: Maverick.”

But Cutting says that it has nothing to do with attention spans — we just know the language of movies better than our ancestors did. “We have gotten, over the decades, a lot faster at picking up visual material,” he said. “It sort of makes sense that a filmmaker would make the shots shorter. The filmmaker doesn’t need to dwell on something like that.”

Cutting also points out that even though TikTok videos are very short, movies themselves are getting longer. “There’re a lot more movies pushing three hours now than there used to be,” Cutting said. “We also have long-form television, where things can go on for eight episodes, 12 episodes, or whatever.”

Hanover Square Press

One thing’s for sure: As Lauren Barnett points out, technology’s not going away: “It’s their whole world. There’s no job where they could be without it. There’s no academic environment where they could be without it. There’s no social interaction, unless they go away to the mountains for two months!”

Professor Gloria Mark said she is not an advocate for throwing away technology: “What we need to do instead is learn how to live with it.”

So, she offered a couple of tips for staying focused:

- First, when you feel the itch to change tasks, analyze why. If it’s just boredom or procrastination, make a deal with yourself to work another 20 minutes, and then treat yourself to a reward.

- Second, picture yourself at the end of the day. What do you want to have accomplished? What do you want to feel? “A concrete visualization of yourself sitting on the couch, you know, watching your favorite show is really good motivation,” she said.

Pogue said to the Barnetts, “My grandfather died just shy of his 107th birthday, and he told me that his parents would say, ‘You’re gonna rot your brain listening to that new-fangled radio.’ For me, it was, ‘You’re gonna rot your brain watching TV.’ For you, it’s, ‘You’re gonna rot your brain on social media.’ Every generation thinks that technology is ruining the next one. That’s why I’m hung up on this notion of, is it worse? Or is it just different?”

“Depends on whether they’re considering productivity, or considering well-being,” said Barnett. “And I think they’re two very different things. I think they’ll be just as productive, but their well-being, with all that increased productivity, there’s no question that their well-being is negatively impacted. So, therein lies the dilemma.”

For more info:

Story produced by Gabriel Falcon. Editors: Joseph Frandino and Chad Cardin.

See also:

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal