When film set designer Ken Adam first read the script for Dr No, the initial film in the James Bond franchise, he was distinctly unimpressed. “At that stage, it was like a small whodunit based on Ian Fleming’s novel, with a chaotic secret-agent plot,” he later recalled of the 1962 spy movie that would eventually earn nearly £50million at the box office.

Adam even turned down the offer of a profit share, opting for a fixed fee instead. “A great businessman I turned out to be,” he later admitted sarcastically after the staggering box office returns. Even his wife, Letizia, had tried to warn him off, fearing it would taint his theatre career. “You can’t possibly do this!” she said. “You would prostitute yourself.”

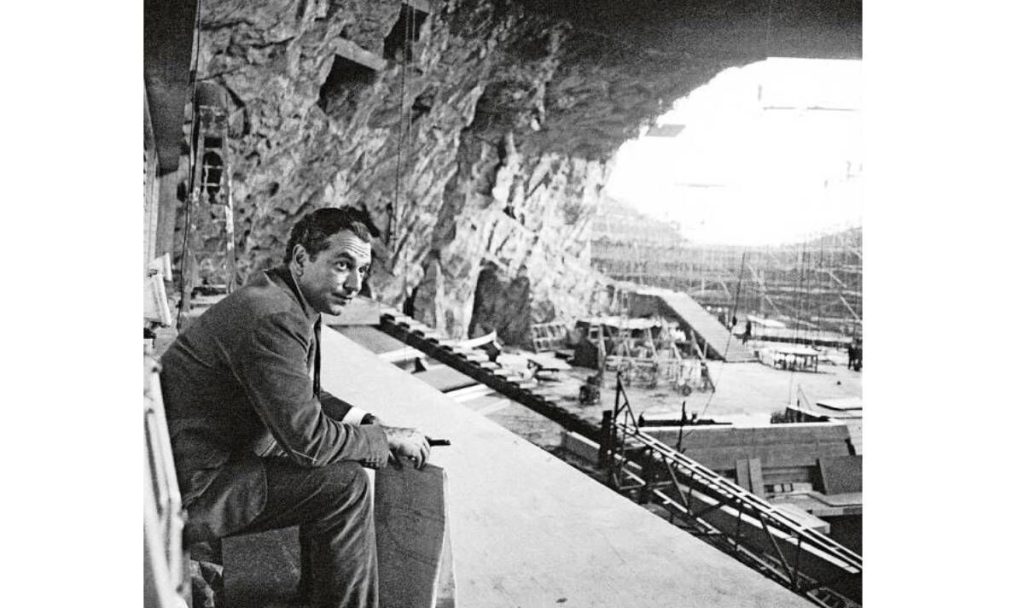

But ignoring his instincts, the German-born designer met with film producers Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman and, despite the limited budget, agreed to join the team. It was the beginning of a relationship with the Bond franchise that lasted for seven films during the 1960s and 70s. Adam was the creative mind behind those unforgettable Bond villain lairs and futuristic hide-outs.

As well as the sets for Dr No, he designed the Fort Knox gold depository in Goldfinger; the dormant Japanese volcano lair in You Only Live Twice, with its vast rocket launcher; the underwater Atlantis in The Spy Who Loved Me; and Moonraker’s futuristic space station.

He also worked on many of the ingenious Bond vehicles, such as the amphibious Lotus Esprit from The Spy Who Loved Me; the Little Nellie gyrocopter in You Only Live Twice; and Sean Connery’s Aston Martin DB5 from Goldfinger, with its wing-mounted machine-guns, protruding wheel scythe, bullet-proof windows, revolving number-plates and, perhaps most memorably of all, its passenger ejector seat.

“All the gimmickry and gadgets were just what I would have wanted in my own car,” Adam later explained. “It got rid of all my frustrations.” Thanks to his inventive designs, other filmmakers were soon scrambling to recruit him.

He would go on to create other film classics such as the war room in Stanley Kubrick’s Cold War comic masterpiece Dr Strangelove and the flying car in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

The story of his life and his invaluable contribution to film design is now told in a beautiful new illustrated book called The Ken Adam Archive. And it turns out the designer’s own life was every bit as adventurous as those of the characters in his films.

Born Klaus Adam, in Berlin in 1921, he fled to England at the age of 12 with his younger brother, narrowly avoiding internment as an enemy alien when war broke out. Six of his uncles and aunts who remained in Germany later died in concentration camps.

By 1941, he had worked his way up into the RAF. “I learned to fly before I learned to drive a car,” he later explained.

Intriguingly, he was one of just three Germans to serve with the RAF during the Second World War. After the D-Day landings, he flew Hawker Typhoons on tank-busting raids into the heart of Germany. “God knows what the Nazis would have done with me if I’d been shot down,” he later recalled. “As a German and a Jew, if I’d bailed out and was captured, that would be the end of me.”

For that reason, he anglicised his first name, changing it to Keith then to Ken. Towards the end of the war his plane was shot down over Holland, forcing him to crash-land. Fortunately he “walked away unscathed”.This early life of peril and adventure was the perfect preparation for the Cold War film sets he would later design for the Bond films.

By the late 1940s he was already working as a draughtsman on theatrical sets. Gradually he rose through the ranks, promoted to production designer on films such as Around the World In 80 Days in the 1950s, Barry Lyndon in the 70s and The Madness Of King George in the 90s.

For the first two of these he won Oscars. Shortly before his death in 2016 aged 95, Adam gifted most of his life’s work to Germany’s museum of film and television.

Its artistic director Rainer Rother writes in the new book: “Few production designers have created worlds as all-embracing and expressive as Ken Adam. For more than 70 films he dreamed up spaces whose captivating nature has branded its way into filmgoers’ memories.

“He contravened the limits of the imaginable in a way that was often highly emotional, at times playful and humorous, and yet always believable, so lending the film visual succinctness and magnetism.”

One of Adam’s greatest fans was architect Norman Foster, who once said: “These spaces – whether it’s the lair in the heart of a volcano, whether it’s a bunker room, whether it’s a car like the Aston Martin or Chitty Chitty Bang Bang – they are branded in our memory, they are enduring, they are powerful, they are spatial, they are heroic. That I think is a great legacy.”

- The Ken Adam Archive by Christopher Frayling is published by Taschen

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal

Latest Breaking News Online News Portal